Homo Ludens is a text frequently cited yet less often read with respect to games and culture. Establishing the concept of the ‘magic circle’, many subsequent studies of games use this work of historical analysis to convey authority and gravitas to the field, and Huizinga’s key message is still a compelling one: that to play is necessary to human life and culture.

This post will shortly be available as a video on the Seriously Learned Youtube channel, meanwhile you can hear Laura talking about Huizinga on BBC Radio 3 here.

Who was Johan Huizinga?

Johan Huizinga was a linguist and historian based at Leiden University when he wrote Homo Ludens in the 1930s. He was particularly interested in the behaviours of courtly life in the medieval, renaissance and late baroque periods, and noted their tendency towards play. However, in scholarly circles in the Netherlands he was a controversial figure and branded a detached recluse for concentrating on telling tales of a beautiful and idealised past, rather than addressing the contemporary dangers of Fascism and Nazism. Nonetheless, anti-Nazi actions he had taken in the 1930s and later criticism of the occupation of the Netherlands had him detained in 1942 and he was subsequently refused permission to return to Leiden. He died in 1945.

Colie (1964) was instrumental in foregrounding Huizinga’s contribution to English-speaking scholars in the post-war period. She highlights that Homo Ludens is not a theory of games, but rather a theory of the function of play in human culture. Colie implies that Huizinga’s work on play is important for recognising that as social beings we don’t only come up with rules to get along together, but also allow for spaces where we can break those rules in order to explore alternative ways of organising.

What is play?

In Homo Ludens, Huizinga points out that Ancient Greek culture distinguished between paidia – lighthearted or child’s play, and agon – sport or games, but to the Romans, all was included in the term ludus – play. By exploring the challenges and contests in Greek sport and identifying the linguistic approach to play in Germanic and Romance languages, as well as Sanskrit, Sinitic (Chinese) and Native American (Blackfoot), Huizinga sides with the Roman characterisation of both types of activity as the same. He identifies that play incorporates descriptions of nature and human action, pretence and limits, freedom of movement and of competition. Most frequently, Huizinga identifies play as comprising a pledge to undergo some kind of risk and tension, even to the degree of deadly seriousness as in violent sporting matches.

The 5 characteristics.

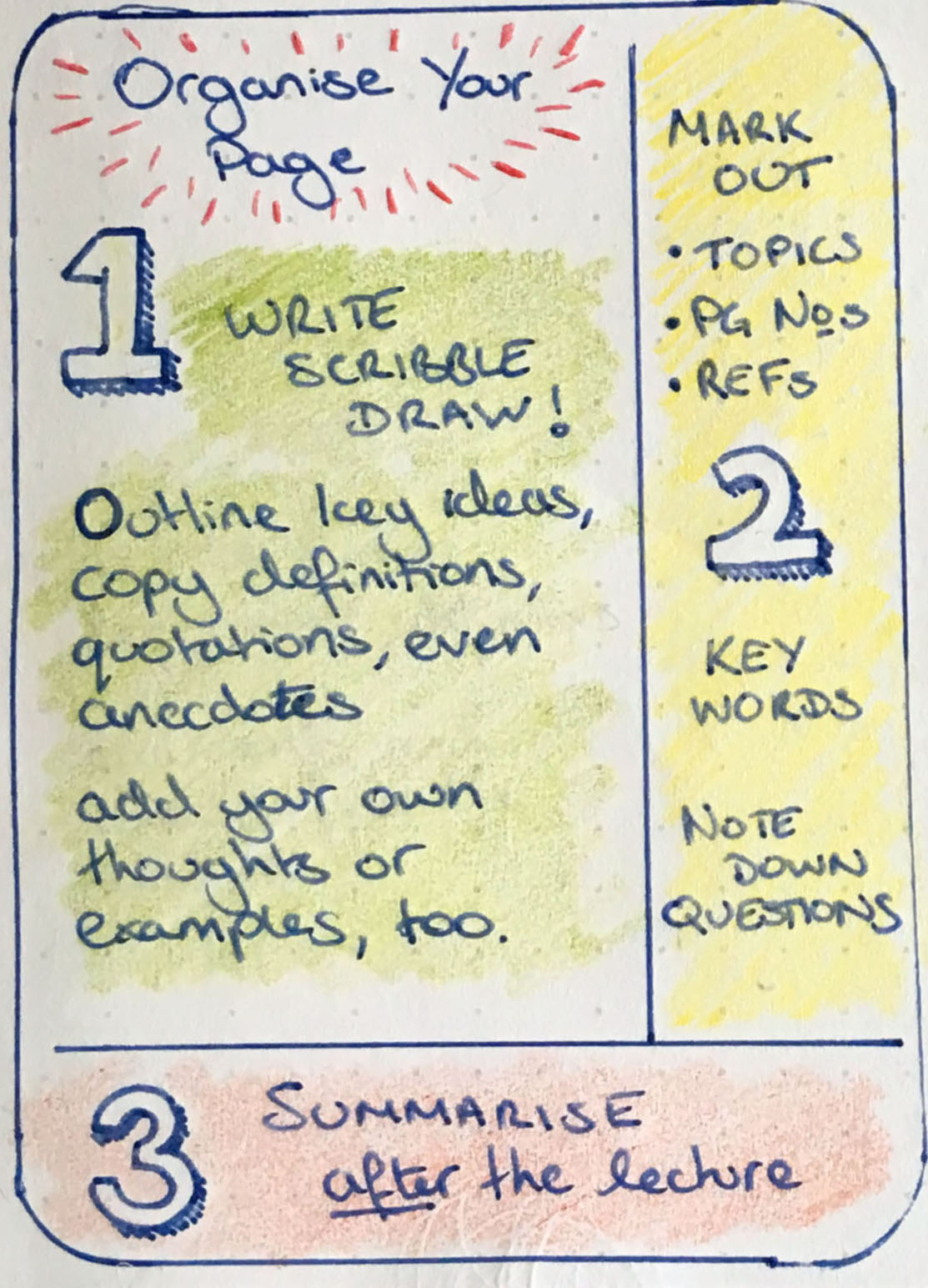

Huizinga outlines five characteristics of play;

Play is a voluntary activity or occupation executed within certain fixed limits of time and place, according to rules freely accepted but absolutely binding, having its aim in itself and accompanied by a feeling of tension, joy and the consciousness that it is “different” from “ordinary life”

1. Play is voluntary

The voluntary nature of play is in contrast to the involuntary nature of the things we must do for survival. This is obvious in tasks such as washing or tending crops but less obvious when we start to consider ‘playful’ activities such as craft or artistry which require toil or training. Huizinga debates this in the distinction between the musical (arts) and plastic (crafts) to argue that while performance is a type of free play which may rely upon expertise and training, the training or crafting of skill or a piece of art is work. In this distinction, the showing of a painting might be play, but the production of it is labour.

2. Play is Rule Ordered

When we enter into play, we agree to play by explicit or implied rules, which are often different to those we normally follow. These rules are rules of behaviour as well as of material significance. For example, the idea of taking turns, and that everyone shall have a turn to act or speak is a frequent unwritten rule of most conversational games. The use of physical tokens to represent action is another frequent rule, along with details such as how many tokens a player has and how actions through them may be performed.

3. Play happens within fixed boundaries: the ‘magic circle’

The setting aside of play as a distinct practice is closely related to the understanding of the specific order and binding rules of play. When we agree to the restriction of rules, we also agree that these restrictions will only apply for a time and/or place. We allow ourselves the freedom to step outside of that space or time, whether loser or victor, and return to a different set of rules of behaviour. Those who breach the boundaries are contemptuous, spoil-sports or barbarians, and are swiftly excluded.

4. Play is different

When we play, we are distinctly aware that what we are doing is not ‘ordinary life’, though we might mimic everyday activities. We inhabit a different ‘mental world’ where there might be consequences to what we are doing, but those consequences usually adhere to different rules. This is one of the main reasons why play can be so satisfying, as we sometimes need to enter a space where the rules are different to everyday life – fairer or more clearly specified, in order to explore why some practices have been successful or unsuccessful.

5. Play is not useful or in a material interest

One of the important elements of play is “what is at stake”. Although gambling and risk-taking are identified by Huizinga as key to understanding the tension and excitement of play, play is nonetheless non-purposeful. Huizinga compares professional and amateur sports in this respect, highlighting that once the playing of a game is subservient to a material interest it no longer can be understood as pure play. However, in conjunction with the concept of the magic circle, it remains possible to identify play as having serious and material consequences without necessarily invalidating its status. Importantly, although satisfaction is key to play, Huizinga’s definition does not rely solely upon a psychological perspective of play as producing a ‘feeling’ of engagement (or flow) as a definitive factor.

Play and Culture

Huizinga explores a wide range of social activities in Homo Ludens that we might not identify as play. These include ‘sporting’ activities such as duels to the death or verbal ‘battles’ such as public debates. He also points out the importance of play to ceremony and performance. Both dance and music are play performances, though we would not often think of these as we do games.

Gifts: Conspicuous consumption and destruction

A significant type of play identified in Homo Ludens is drawn from Mauss’ work on gift-exchange, which shares similarities with Veblen’s work on conspicuous consumption.

one proves one’s superiority not merely by the lavish prodigality of one’s gifts but, what is even more striking, by the wholesale destruction of one’s possessions just to show that one can do without them.

This highlights how the practice of giving away high-value items conveys a message regarding the wealth and virtue of the gift-giver, and places an obligation on the receiver to reciprocate, or in the case of the destruction of property, to compete.

This type of competition compares with boasting or slanging matches, and is labelled a ‘squandering match’ by Huizinga. The expression of excessive politeness is a comparable reversed game to that of the boasting match, in which each participant strives to be more courteous than the other.

Knowledge: play to learn

Just as there are forms of contest based on chance, dexterity or physical ability, Huizinga points out the common occurrence of knowledge contests in history and myth. Knowledge contests also remain so central to contemporary life we don’t even recognise them as such – though we call them ‘tests’ and ‘qualifying exams’! In Homo Ludens, Huizinga focuses on the role of wordplay and riddles in schooling particular types of thinking or expertise.

The answer to an enigmatic question is not found by reflection or logical reasoning. It comes quite literally as a sudden solution – a loosening of the tie by which the questioner holds you bound. The corollary of this is that by giving the correct answer you strike him powerless. In principle there is only one answer to every question. It can be found if you know the rules of the game.

While this resembles being quizzed in front of a class, the riddle-question can also push the limit of knowledge by motivating participation in the challenge. Huizinga presents the example of the ‘superlative question’ game, such as “what is sweeter than…” where each answer become the next question. To answer “I don’t know” is to lose the game, so it motivates scholarship. If we take a different version of this question, such as “what is smaller than…” our eventual result today would be to study advanced mathematics or particle physics!

Law: the courtroom as a ‘magic circle’

the lawsuit can be regarded as a game of chance, a contest, or a verbal battle

When we consider the seriousness of a court of law, Huizinga’s assertion that we can identify law as a type of play seems an extreme one. It relies upon the recognition of historical and cultural approaches to justice which rely upon the setting aside of a context in which a trial may be fairly conducted. The pursuit of justice must be set apart from other social activity in order to establish principles of fairness, and as such it utilises the characteristics of a play contest. This setting-apart of the courtroom also applies to the judge and other roles within it – as these individuals must set aside personal attitudes and concerns. This presents some explanation, Huizinga suggests, for the peculiar use of costume or regalia in the legal profession.

Play and War: worlds apart?

Its principle of reciprocal rights, its diplomatic forms, its mutual obligations in the matter of honouring treaties and, in the event of war, officially abrogating peace, all bear a formal resemblance to play-rules inasmuch as they are only binding while the game itself – i.e. the need for order in human affairs – is recognized.

If we look to ancient civilization it is not difficult to find a link between violent sports and the training of skills for war. From ancient strategy games to contemporary computer games, the theme of warplay is a popular one. Unlike the moral panics which propose that warplay encourages violence, Huizinga proposes that the limiting rules of play are fundamentally necessary to distinguishing between human engagement in war, an aggressive combat between equals, and animal violence in the pursuit of survival.

Implicit to Huizinga’s writing on this seems to be the proposal that war without limitations is a challenge to all human civilisation; war without limitations is not an activity that may be claimed by homo sapiens without placing that very categorisation in jeopardy.

We might, in a purely formal sense, call all society a game if we bear in mind that this game is the living principle of all civilization.

Is everything play?

Since Huizinga, other influential scholars have presented definitions of play which make different distinctions. Caillois’ Man, Play and Games (1961) reintroduced the distinction between ‘play’ (imaginative fantasy) and ‘sport’ (skill-based games), while some psychologists have proposed a definition of ‘unstructured’ play as the individual experience of creativity or improvisation.

Purposeful play, or the appropriation of play-like characteristics to activity which is not different to “ordinary life”, for Huizinga, is false play. In the final chapter of Homo Ludens, Huizinga expresses concerns about the use of play to conceal political or social agendas or to promote ‘barbaric’ tendencies such as the infantilisation, subjugation or oppression of others.

Overall, Homo Ludens highlights how many cultural activities incorporate play-like characteristics, and also indicates that new cultural practices can emerge from playing with existing norms and formats. Yet Huizinga makes no assumption about the quality of play activity; suggesting that it can be debased to meaningless repetition, or can be elevated to ritual or sacred status. Where play offers scope for development and improvisation of culture, it may be seen as a productive force. Yet some characteristics of play may be employed to inhibit the development of collective culture, and the victories achieved through play are empty ones.