Back in July I attended the Critical Management Studies conference in Liverpool, an interesting experience as it was very close to home (unlike last year’s hike to the USA) and also my first attempt at attending a conference when presenting more than one single-authored paper. While I usually find that conferences are tense affairs until after my presentation is out of the way, the need to be prepared for two paper presentations incentivised me to be very organised for this conference and plan my materials and outlines well in advance. I was also co-convenor of a stream, though as two streams were merged we had plenty of support in organising things. We really needed it, as the conference venue was a beautiful period building (The Adelphi in central Liverpool) but with somewhat compromised facilities when applied to this conference format, and a confusing layout of rooms and corridors at times reminiscent of the Overlook Hotel.

I agreed to present one of my papers at an internal university event only a few weeks prior to the conference which really helped refine my thoughts on the contribution of the paper and I felt nicely confident about conveying the message (if not, perhaps, in the specified timeframe of 20 minutes). This paper explored the possibility of more humane and dignified work relations that might be promoted through turning to rewards based crowdfunding, as the process could encourage workers and organisations to think about their ‘backer’ communities and other stakeholders in a new way. I hope to begin an empirical project on this soon. The stream more broadly included research into how workers are negotiating the digital-analogue interface of app-enabled working, coworking spaces and other forms of innovation and meaning-making around platform capitalism. There were some great papers and I was really pleased with how the stream turned out.

In contrast, however, I heard many colleagues were very dissatisfied with the conference. This was partly instances of poor planning or lapses in organisation of the conference (registration and the lunch buffet each day were chaotic for the number of delegates and the conference dinner venue too prone to echoes to hear the speeches), but also a concern that much of the conference had become hostage to academic performativity. Such a claim is especially tense given that CMS as a scholarly community has been critiqued for its anti-performative stance § , but we ought to distinguish between the published narratives of CMS academics or actions taken in the service of their research ambitions with participants and the performative acts of the community as scholars policing their own boundaries and subject to their own managerial scrutiny.

At the root of colleagues dissatisfaction seems to be the question; what are conferences for?

- meeting scholars with similar interests

- engaging in scholarly discussions

- keeping up to date with developments in the discipline

- maintaining or reviewing the objectives of a distinct scholarly community

- presenting research-in-progress to peers for comment and feedback

- challenging unconventional methodologies

- disseminating results from completed research projects

- obtaining support or solidarity for politically unfashionable research topics or agendas

- reinforcing academic status or position

- improving manuscripts pre-submission for publication

- proposing ideas for special issues to editors of journals

- maintaining your influence or brand image

- learning or reinforcing norms and expectations about an academic career in the discipline

- commissioning content for special issues of journals

- influencing or controlling debate through exclusion

- finding out about upcoming job opportunities

- meeting the requirements of a funder

- demonstrating research activity or influence to your university

The above list suggests a range of ambitions for conference participation, some of which may surprise you. However, despite the ideal of an academic conference as a venue to test ideas and progress knowledge, they have increasingly also contributed to the performative outcomes required by university managers. Conferences as regular features of the academic landscape also play a substantial part in reinforcing dominant power relations; notable concerns at this conference from i) the pre-conference critique on mailing lists of the requirement in the call for stream proposals that planned outputs such as a journal special issue would be expected as part of the application and ii) organising by the women in academia CMS support network VIDA to encourage submissions and activism to address and expose the integrated performative heteronormativity at the conference.

Activity that seemed to fit within the more instrumental or discriminatory practices in the above list was upsetting for some. In the environment of CMS in UK academia that has begun to feel uncertain post-Brexit thanks to the strategic cuts at some universities and threats of them at others, the anti-performativity of CMS is a justifiable worry. Such an approach results in fewer opportunities for ‘impact’ – an area in which it is expected that management and business schools should excel. However, it is also the case that actions within the community to exclude or fail to approve the work of marginal scholars, or to attempt to replicate the behaviours and paradigms of ‘macho business’ or ‘hard science’ in order to validate scholarly activity in the eye of university management can only be to the detriment of the discipline. This is particularly so in a discipline which spends much of its energy critiquing such behaviour elsewhere. Consequently it was especially refreshing and energising to see these concerns being aired in the intervention by some scholars in the form of development of a game of solidarity/bullshit bingo.

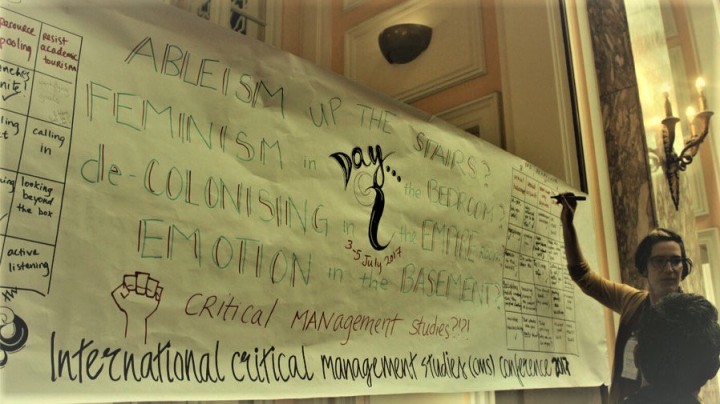

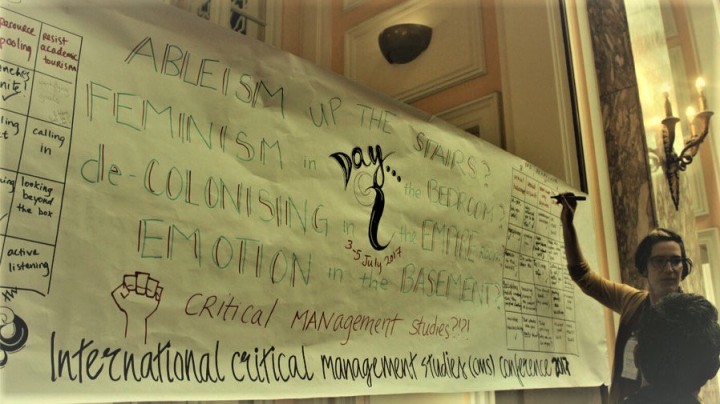

The conference organisers had engaged an illustrator to record the conference (her output is shown in the header picture) and I was personally very excited to see the overviews come together. Yet again, however, engaging an illustrative artist with no grounding in the intellectual debates of the field characterises the activity of illustration as an archival one. While it may make the content more accessible, this objective is in service once again to academic performativity rather than to enhancing understanding of the material. The illustrator, however, consented to some of her materials being appropriated in the production of this poster:

For me, the beauty of this poster lies in it’s action to call out the discrepancy between the topics acknowledged as significant to the scholarly community of CMS and its internal actions; streams of research papers were running on ableism, feminism, de-colonialisation and emotion in organisations. Yet in the co-ordination of the conference these very issues had not been addressed. Furthermore, the many features appearing on the bingo boards as evidence of scholarly ‘solidarity’ (e.g. active listening to research presentations, encouraging introductions) or of academic ‘bullshit’ (e.g using Q&A time to tell everyone that your work is of key relevance to them and should be cited instead of engaging in constructive criticism) were being foregrounded by the poster and the game.

All in all, the CMS community, like the broader academic community, may well be in difficult times and have numerous internal tensions over solidarity and action that need to be resolved. Although conferences like these remind us of these tensions, I was extremely pleased to see and support interventions and activism that encourage us to reexamine our priorities and actions with an ambition to forge a better type of scholarly engagement with problems inside and outside of the university.

§ An introduction to the current state of this debate can be found in the recent special issue on critical performativity published in M@n@gement with the remarks from the editors available here